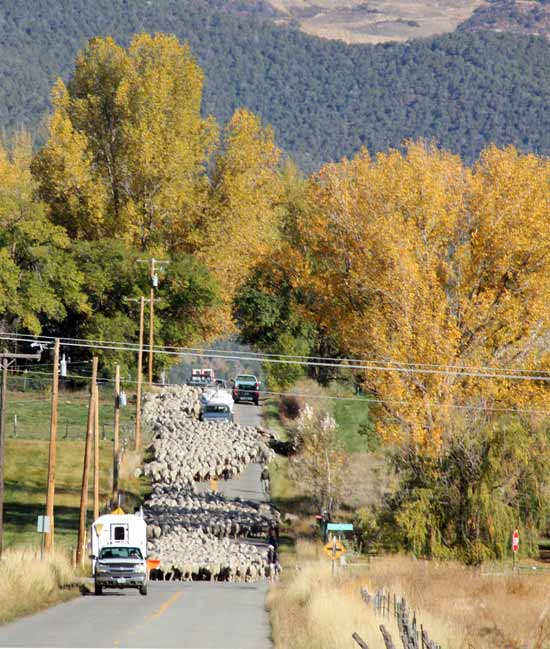

“The sheep are on the move!” Patrick announced. We had heard about these biannual migrations and didn't want to miss out on the spectacle. So when he dropped in to Oogie and Ken McGuire's Desert Weyr farmhouse in Colorado, we were ready.

All things considered there aren't that many sheep in the USA. Sheep are difficult to count, not least when you are trying to get to sleep! It depends what time of year you gather your information; lambs born in the springtime may be eaten before they become an annual statistic so it is more meaningful to compare breeding ewes. But as a rough comparison it is worth considering that although the human population in the States is around five times that of the U.K., there are only twice as many sheep being farmed in an area almost forty times that of ‘Old Blighty’. An awful lot of Americans can get through life without even seeing, let alone eating a sheep and this is one reason we were keen to watch them run through Paonia and on to lower pastures.

Ten minutes later we turned off towards the town, and although there were none to be seen, traces of the flock’s passage were evident on the road. We headed on south west in the direction of The North Fork Gunnison River, following alongside the railway track, now operating solely for hauling coal. There in the distance we caught sight of the tail shepherd and his dog, following in the wake of the jangling sheep bells and thousands of hooves. As we edged our way carefully alongside the end of the trail, stragglers pulled at the parched grass on the roadside, only to be urged along by the shepherds. The handlers come from Peru, making good money in the season to send home to their families. Pushing slowly on we eventually reached the lead vehicle parked way up ahead, a mobile shepherd hut and welcome overnight refuge for the men accompanying the flock. Today they will cover up to ten miles and the whole journey of three or four days will find the flock on a ranch some 30 miles from where they started.

With the road clear we sped on and chose a vantage point to park. Eventually the flock trotted over the hill towards us, pausing nervously when barking guard dogs at a neighbouring farm halted their progress. Then they were off again, toes tapping, bells jangling nose-to-tail on their journey. These Fine Wool sheep are mostly Rambouillet, a breed that is an equally good producer of meat and wool and which first came to the U.S in 1800 from the estate belonging to the French King Louis XVI. He had received a gift of a few hundred Merino sheep from his Spanish cousin, also named Louis, in the 1780s. (It was the Moors who had first brought Merinos from North Africa way back in the C14th when they invaded Spain, leaving them behind when they fled). The French King had an experimental farm at Rambouillet and so the breed was developed and named appropriately. These big, sturdy sheep are hardy and adaptable, the rams weighing up to 135kg. Ewes tend to lamb easily and are good attentive mothers with abundant milk. These factors together with a strong flocking instinct and their North African ancestry make them especially suited to open range conditions.

Every so often the flock running by was punctuated by a black sheep. Ranchers follow the practice of including a black one for roughly every hundred white to act as a marker. Out on the ranch it’s far more practical to count the black ones for a quick estimate of how many hundreds are surviving in a landscape where predators abound. Almost five minutes passed while the 2-3 thousand sheep ran by, with the last guardian dog bringing up the rear. It was going to be a long few days for everyone on the road.

Joe Sperry's sheep transporter

But of course not all American sheep walk to their winter grazing. Oogie had arranged for us to visit a ranch up past Somerset coal mining country and a couple of days later we were climbing through the rock strewn highway to Joe Sperry’s place. But what a contrast this was from the farming set-up at the McGuire’s Desert Weyr farm The distant views are just as beautiful, the farming is different. Joe’s house sits at 7700 feet surrounded by a mere 326 acres of irrigated sage brush, oak and aspen. (The now affluent ski resort town of Aspen is nearby and takes its name from the local silvery grey barked trees that abound in the area and, those of a certain age, may remember it as where the late John Denver made his home). But this is neither Joe’s only home nor the sole acreage his animals graze. Each autumn Joe packs up the house and moves himself and his Polypay breeding ewes fifty odd miles for overwintering to the 300 hundred acre farm at Delta, almost 3000 feet lower in altitude. We arrived just ahead of the massive, four decker transporter that was to take the last batch of sheep on their journey. The huge lorry manoeuvred in place while the Polypays waited quietly in their pen. On the horizon the distant snow topped Mount Gunnison rose majestically while somewhat incongruously, on the neighbouring farm, an exploratory fracking drill worked away.

Loading sheep on the four-decker at Joe Sperry's farm

Polypay sheep are, in the history of breeding, a very recent creation. Research in the 1960’s led to the production of this four breed composite, developed as an efficient duel purpose animal. Since the 1970s Polypays have become popular across America, being highly efficient producers of both (poly), meat and wool, and so yield lucrative returns (pay). The ewes are highly prolific, they are good mothers, capable of nurturing two crops of fast growing lambs each year and known for their hardiness. They fit well in this dry, mountainous environment. We watch as the sheep are loaded, deck by deck, before the transporter lumbers off down the dirt road.

Joe Sperry, sheep farmer, Colorado

Joe’s shepherds have travelled from Mexico, they are experienced and reliable and load the sheep with minimum fuss. Their deal means they are able to save money to send home and have return flights at season’s close. Outlying farm areas are patrolled on horseback where they must be ever alert to predator threat.

Over a picnic lunch in the late October sunshine Joe tells us what it's like to farm here amongst the stunning scenery. He has permits to graze his animals in the 30,000 acres of forest where over a thousand bears reside and coyote, deer and mountain lion abound with all the challenges this brings.

“I happened upon a recent kill,” he tells us over his salami sandwich, “and watched as a mountain lion popped a ewe over its shoulder and off it went straight up a cedar tree with it, as easy as pie!”

Joe Sperry's ranch country

As we packed up a group of men arrived, offloading their rifles and hunting gear. They had come for the seasonal hunt and would spend the next couple of days in a group ranging on horseback looking out for deer and elk.

As we made our way back to Desert Weyr farm, I mulled over all I had learnt in the last few days in this part of Western Colorado, the often demanding physical environment for people making a living, the differing scales of farming, the role of migratory workers, intervention in our animal’s genetic make-up, the importance of maintaining a diverse gene pool in our domesticated animals and the need for sensitivity in our use of natural resources.

I couldn't help feeling more comfortable with the set up at Ken and Oogie McGuire’s. After all you can count sheep but take care that you make sheep count.

Carolyn Kennard